-

5. Instruments mitigating external vulnerability (FFAR, FECR, IFR)

-

7. Capital buffer of systemically important institutions (OSII-B)

-

11. Financial stability risks of climate risk and options for their macroprudential management

-

12. The systemic significance of cyber risks and the potential risk management options

1. Executive Summary

The MNB describes and evaluates the functioning of its macroprudential instruments – covering its resolution and consumer protection processes as well –, along with market participants’ adaptation, in its yearly Macroprudential Report. In October 2025, the following main messages can be formulated:

1. The MNB has required the maintenance of a 1-per-cent positive neutral Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB) for domestic exposures since 1 July 2025, as is justified in a neutral cyclical risk environment, widening the MNB’s macroprudential leeway and strengthening banks’ resilience. A low and stagnating level of cyclical systemic risks is identified at present, which does not justify a CCyB rate exceeding 1 per cent; however, the medium risk inherent in collateral values – which may potentially increase in the future – calls for close monitoring. The maintenance of the current rate is also justified by the domestic banks’ strong capital position and their ability to accumulate capital, enabled by their favourable profitability ratios.

2. In response to increased real estate market risks, the MNB modified the regulation in September 2025 to strengthen the forward-looking and preventive nature of the Systemic Risk Buffer (SyRB) by activating two sectoral SyRBs (sSyRBs) instead of the existing SyRB requirement targeting project loan exposures collateralised by commercial real estate. The MNB imposed a 1-per-cent rate on domestic residential real estate-backed, as well as domestic commercial real estate-backed exposures to domestic counterparties, with effect from 1 January 2026.

3. The MNB did not change the list of other (domestic) systemically important institutions (O-SIIs) in its 2024 review either, and left their individual buffer rates also unchanged for 2025. Changes in the systemic importance and concentration of the O-SII banks remained modest last year. The buffer rates are assessed proportional in international comparison.

4. Households over-indebtedness cannot be identified last year, in spite of an upswing in lending activity. However, as regards new residential mortgage lending, a persistent price increase in the housing market is causing borrowers’ income burden to grow. Looking forward, the Home Start Programme continues to drive demand for household loans and lending dynamic, necessitating increased monitoring. The increased real estate market risks are mitigated by the MNB through the adoption of a comprehensive regulatory package. As part of the package, the nominal thresholds prescribed in the borrower-based measures will be modified as of 1 January 2026, while the requirements applying to the loan-to-value ratio for first-time home buyers were modified with effect from September 2025 in order to make the lending processes smoother.

5. The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) – which ensures the banking system’s short-term liquidity – was at a stable high level during the past year, although with a modest decrease in the liquid asset surplus. The Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) requirement is met by the banking system with a modestly decreasing stable funding surplus in connection with the increase in the credit portfolio. To improve the transparency of the crisis management processes the MNB, like some other central banks, is assessing whether communication of certain elements of the central bank’s Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) through its website, as well as directly to the institutions, may help avoid the stigmatisation of banks and thereby retain investor confidence.

6. Banks continue to meet the macroprudential funding requirements - on-balance sheet FX positions, maturity mismatch and excessive dependence on risky corporate funding -with adequate buffers and in healthy funding structures. The banking system’s short-term external debt as a proportion of its balance sheet total remains low.

7. Banks comply with the Mortgage Funding Adequacy Ratio (MFAR) regulation with safe buffers. The past year has seen a further increase in the amount of mortgage bonds issued by domestic mortgage banks. The proportion of foreign currency mortgage bonds increased considerably, mitigating concentration risks by promoting ownership diversification. A material increase is expected in the amount of mortgage loans and mortgage bonds as a result of a likely substantial expansion in housing loans in connection with the Home Start Programme; therefore, the stable financing of the growing loan portfolio will be of essence. Partly in response to this, the MNB has adopted a decision on fine-tuning its regulation to strengthen sector-level stable fund raising and the liquidity of the mortgage bond market, as well as to help with banks’ adaptation.

8. Credit institutions have, since 1 January 2024, been continuously meeting the mandatory MREL requirements set by the MNB. There has been a moderate shift at the institutions concerned from equity-type MREL-eligible resources towards MREL-eligible bonds. The MNB closely monitors the volume and concentration of MREL-eligible bonds sold to household customers and may introduce restrictions in this market if necessary. The central bank tested the feasibility of the resolution plans first based on liquidity data submitted by the institutions, and further testing of feasibility will be carried out on a continuous basis. The development of alternative transfer resolution tools is a new element in resolution planning besides creditor recapitalisation (bail-in).

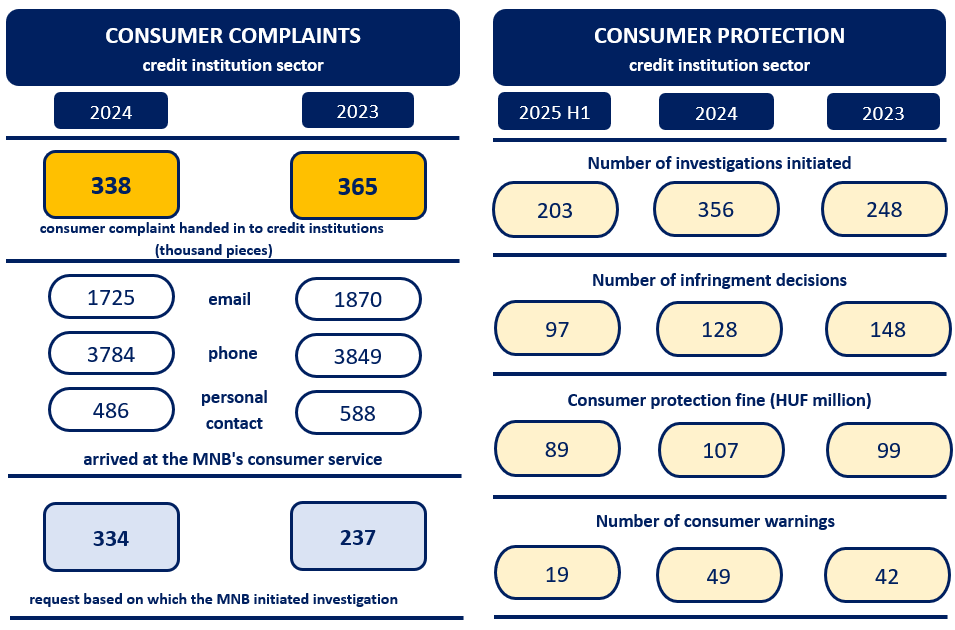

9. The number of credit institution clients applying for the MNB’s consumer protection procedure declined in 2024. The MNB identified deficiencies in the information provided by institutions prior to the termination of mortgage loan contracts affected by payment delays. In response to the increase in the number of payment service offences during the past period, in its capacity as an authority, the MNB places particular emphasis on preventing financial crimes. The increasingly widespread use of so-called buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) facilities pose limited financial stability risks but considerable consumer protection concerns; therefore, the expansion of such services requires close monitoring.

10. The systemic risk monitoring of corporate credit exposures subject to climate transition risks indicates a modest decrease in the proportion of vulnerable exposures in the banking system. Improvements in the energy efficiency of domestic properties have, since 1 January 2025, been promoted by the MNB by way of a green differentiation of the borrower-based measures, in addition to the central bank’s supervisory toolkit. The modification provided targeted support for the growth of green lending without increasing the risks.

11. In the wake of the accelerated digitalisation of the financial sector, cyber risks have evolved into a systemic threat to financial stability, for which the authorities must prepare by comprehensive regulatory actions in response. This includes the system of macroprudential stress tests aimed at exploring the potential systemic impacts of major cyber incidents, supplementing the regular threat-based testing of the digital resilience of financial organisations under the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) of the European Union. The future detailed elaboration and regular execution of such tests, together with the MNB’s “five strikes” initiative, are going to contribute to the strengthening of financial stability as well, in addition to the protection of individual customers and institutions through assessing and enhancing cyber resilience.

2. Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB)

In a neutral cyclical risk environment, the MNB has required the maintenance of a 1-per-cent positive neutral Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB) since 1 July 2025. This measure enhances banks’ resilience and, by increasing the volume of releasable capital requirements, considerably widens its macroprudential leeway in times of crisis. By the end of June 2025, positive CCyB rates had been announced in 25 EEA countries. Currently, Hungary faces a low and stagnating level of cyclical systemic risks, which does not warrant a CCyB rate above the 1 per cent applicable in a neutral risk environment. Maintaining the 1-per-cent CCyB rate is further supported by the domestic banks’ strong capital positions and their capacity to accumulate capital, underpinned by favourable profitability ratios.

2.1. Cyclical systemic risks have been stagnating at a low level during the past year, which have not justified the imposition of a higher-than-1-per-cent CCyB rate

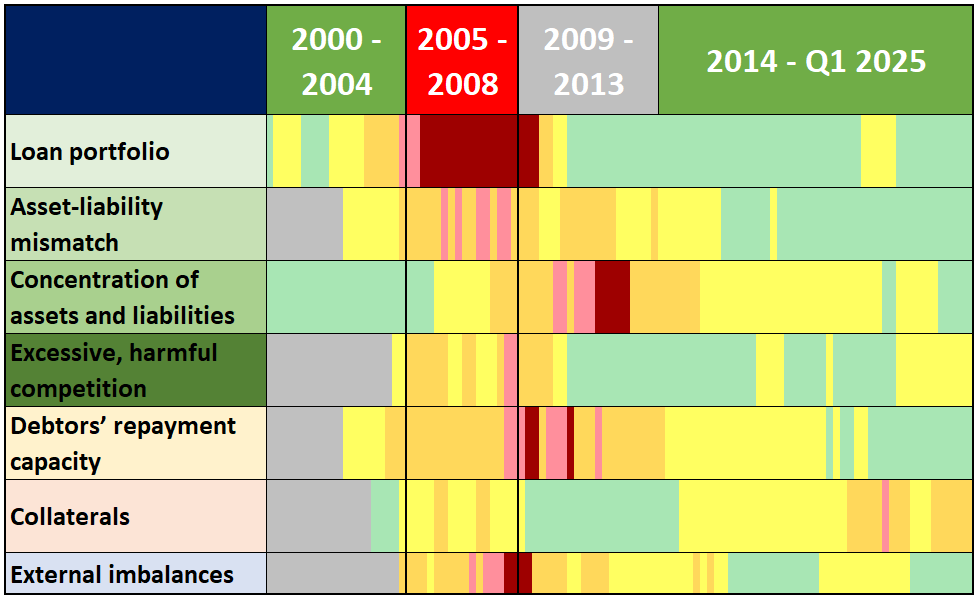

The Cyclical Systemic Risk Map (CSRM) has, during the past year, been showing cyclical systemic risks stagnating at a low level, with increasing risks – jeopardising financial stability – in the categories measuring excessive competition and overvaluation of investment instruments (e.g. collateral) (Chart 1). The “excessive competition jeopardising financial stability” category is indicative of a modest (yellow) risk, primarily as a consequence of the low level of household lending margins and the high levels of bank profitability. The indication of an increase in risks is justified by the fact that the low interest margin and the high profitability are not sustainable and might entail excessive market risk taking. However, current risk predictions are indicative of low housing loan margins relative to the funding costs, stemming from the prevailing higher interest rate environment, along with strong profitability and not overly excessive risk appetites, resulting from lenders’ “interest coverage” enabled by a high ratio of deposit financing. In other words, banks compensate for low lending margins by paying low deposit rates. In the medium (orange) risk “overvaluation of investment instruments” category, indicators (collateral) linked to housing market risks, and those measuring households’ investments in risky financial instruments, particularly investment funds, have increased somewhat. According to the CSRM indications the elevated housing market risks may persist even in a longer run, and they continue to call for increased monitoring.

Chart 1: Development of average values of risk indicators within CSRI risk groups

Source: MNB

The Cyclical Systemic Risk Index (CSRI) has remained near its average value in across observation periods since 2022, indicating a neutral level (Chart 2). Among the eight most important cyclical systemic risk indicators underlying the CSRI, the MNB house price gap indicator and the indicator measuring households’ investments in riskier financial instruments – particularly investment funds –, signal elevated risks, while the remaining indicators reflect lower risk levels. Looking ahead, a gradual improvement in the macroeconomic environment and an upswing in lending are expected along with growing cyclical systemic risks.

Chart 2: The development of the CSRI

Note: The CCyB rate is a rule-based rate determined based on the CSRI, from which the MNB may deviate if necessary, taking into account the indicators of the CSRM and other relevant factors. The lower and upper thresholds are the 7th and 9th deciles of the CSRI values. The box-plot chart on the right depicts the minimum, maximum, interquartile and median values of the historical distribution of the CSRI. Source: MNB

In view of the overall low level of the cyclical risks, the MNB decided to maintain the CCyB rates for domestic exposures in its quarterly rate decisions throughout 2025, as there was no justification for setting rates above the positive neutral rate. The MNB kept the 0.5-per-cent CCyB rate in place, which had been applicable since 1 July 2024 and confirmed its decision to apply a 1-per-cent CCyB rate in a neutral risk environment from 1 July 2025, maintaining this level from 1 October 2026 as well.

2.2. In view of the uncertain environment, EEA countries are raising CCyB requirements

Due to the increased financial stability risks, most EEA countries are increasing their macroprudential capital buffer requirements. The 1-per-cent CCyB rate in place since 1 July 2025 in Hungary is considered average in international comparison. By end-June 2025, positive CCyB rates had been announced in 25 EEA countries. Five EEA countries continue to apply a 0-per-cent CCyB rate, while all CEE countries have introduced a positive CCyB rate (Chart 3). 17 EEA countries apply or plan to introduce positive neutral CCyB frameworks for local exposures, with rates ranging between 0.5 per cent and 2.5 per cent. However, most CEE countries apply a 1-per-cent positive neutral rate. Five countries maintaining a 0-per-cent CCyB rate for local exposures, primarily due to declining cyclical risks and negative credit-to-GDP gap ratios, while some of these countries apply systemic risk buffers (SyRB) to their total exposure values.

Chart 3: CCyB requirements for exposures in EEA countries (June 2025)

Note: Buffers which were announced but not necessarily in effect. CCyB rates shown are for exposures in the country. *Countries that apply a framework that can be considered a positive neutral CCyB rate. Source: ESRB, websites of national authorities

A significant proportion of domestic institutions’ consolidated CCyB requirements is consists of CCyB requirements imposed by other countries. An institution-specific CCyB rate is calculated as the weighted average of the rates applicable based on the geographical location of the counterparties associated with significant credit risk exposures faced by the institution. Domestic banking groups – particularly those with Hungarian parent companies – are active not only in Hungary but also in cross-border operations through subsidiary banks in other EU countries and third countries. Positive CCyB rates are in effect not only in an increasing number of EU Member States but also in third countries that are important to the domestic banking system. Consequently, by 30 June 2025, nearly 64 per cent of the CCyB set aside in the domestic banking system had to be generated by domestic banks in relation to international exposures. The total amount of CCyB in the domestic banking system has been rising since 2023, driven by the continuous increase in capital requirements linked to domestic banks’ significant EU exposures. This was further reinforced by the introduction of a positive neutral CCyB rate for domestic exposures – 0.5 per cent from 1 July 2024 and 1 per cent from 1 July 2025 (Chart 4). Considering the 1-per-cent domestic CCyB requirement and excluding any potential increase in non-domestic rates, the total CCyB now originates in nearly equal proportion from domestic and non-domestic exposures. Nevertheless, even after the introduction of the domestic CCyB rate, the specific CCyB burden on domestic exposures remains lower than that on international exposures (0.82 per cent vs. 1.07 per cent). This decreased difference weakens the incentive to adapt, although it does not rule out a gradual – and so far not widely observed – portfolio restructuring toward countries with materially different CCyB rates.

Chart 4: Development of domestic and non-domestic CCyB

Note: Only the increase in the Hungarian rate from 1 July 2025 is taken into account, not the possible expected change in the rates of other countries. The difference between the applicable domestic CCyB rate (1 percent) and the domestic CCyB rate proportional to the TREA is due to the fact that when calculating institution-specific CCyB rates, the CCyB rates related to individual country exposures must be weighted not by the TREA, but by the credit risk exposures to be taken into account in the CCyB rate calculation, thus the difference is explained by the different distribution between the TREA and these credit risk exposures. Source: MNB

2.3. Banks’ strong capital position ensures lending capacity remains unaffected

Owing to banks’ robust capital position and profitability the imposition of a higher capital buffer does not materially weaken their lending capacity. Based on the capital position as of 30 June 2025 – and considering the increase in the domestic CCyB rate from 0.5 per cent to 1 per cent effective from 1 July 2025, while assuming all other factors remain unchanged – approximately HUF 2,600 billion free capital, including uncapitalised interim profits is available at sector level (Chart 5). The full utilisation this amount could support the disbursement of household and corporate loans totalling around HUF 33,000 billion, assuming the household-to- corporate exposure ratio and average risk weights remain fixed, and that the TREA increase can be absorbed using the free buffer. The 1-per-cent CCyB rate – raised by 0.5 percentage point and effective since 1 July 2025 – may result in an additional capital requirement of HUF 115 billion. Its impact on mortgage loan interest rates, assuming a 35-per-cent favourable risk weight and a 12-per-cent cost of capital, would be negligible, estimated at 0.04 per centage point increase on average.

Chart 5: Development of macroprudential capital requirements and the capital position

Note: Estimate focusing solely on the change in combined buffers, ignoring other additional supervisory capital requirements affecting free buffers (e.g. potential change in Pillar 2 capital, P2G, etc.) and the MREL requirement, as well as expected changes in lending and profitability. Not considered profit: the non-recognized part of the mid-year or year-end profit. Source: MNB

BOX I: Quarterly CCyB rate decisions supported by MNB’s revised cyclical system risk monitoring system since December 2024

Based on its June 2024 decision, the MNB determines the applicable CCyB rate to institutions using the prevailing benchmark CCyB rate, the positive neutral CCyB rate of 1 per cent (applicable since 1 July 2025 in a neutral risk environment), and all other relevant factors.

Chart 1: The process of the quarterly CCyB-rate decisions

Source: MNB

The MNB has, since 2024 Q4, been making decisions on the CCyB rate for domestic exposures based on revised methodology. Accordingly, the MNB has extended and restructured the so-called cyclical systemic risk map (CSRM) used to monitor changes in domestic cyclical risks, on this basis, developed the cyclical systemic risk index (CSRI).

The new CSRM tracks 58 indicators – significantly more than the previously version - providing a more comprehensive picture of cyclical systemic risk developments. The CSRM presents the indicators in a renewed structure: (1) credit institutions, (2) borrowers, (3) investment instruments (collateral) and (4) international categories, further broken down into sub-categories. Risk indicators have been classified using colour codes: low (green), moderate (yellow), medium (orange), high (pink) and persistently high (red).

To facilitate interpretation, the CSRM indicators are aggregated in a single measure, called the Cyclical Systemic Risk Index (CSRI). A so-called Growth-at-Risk (GaR) model was first estimated to identify the indicators that best predictions potential domestic real economic crises over an 8-quarter horizon.1Subsequently, the selected indicators were aggregated using a factor model. The final index is calculated as the average of the resulting three most significant factors, weighted by their explained variance ratios.

As part of the renewal of the cyclical systemic risk monitoring system, the so-called benchmark CCyB rate, which is determined by cyclical risks, has been calculated since 2024 Q4 based on the CSRI instead of the additional credit-to-GDP gap. The CSRI enables a more accurate and less uncertain measurement of cyclical risk growth compared to the previously applied additional credit-to-GDP gap, reducing regulatory uncertainty (inaction bias) through more reliable predictions, and allowing earlier and quicker establishment of the CCyB requirement. The MNB calculates the benchmark CCyB rate by considering both the rule-based rate which is derived from the CSRI and the CSRM indicator signals.

The MNB has improved the transparency of its CCyB decisions by publishing the underlying indicators. The MNB informs the public about its CCyB decisions by disclosing the methodology used to determine the CCyB, through press releases, publishing the underlying professional justification and, since 2024 Q4, by publishing the values of the indicators underlying the decisions, along with the aggregated risk indicators for the relevant indicator groups, in the form of time series.

3. Borrower-based measures

Households over-indebtedness cannot be identified last year, in spite of an upswing in lending activity. However, in the case of new residential mortgage lending, an increase in borrowers’ income burden is being observed in connection with a persistent price increase in the housing market. The Home Start Programme may continue to drive demand for household loans and lending dynamic, necessitating increased monitoring. The increased real estate market risks are mitigated by the MNB through the adoption of a comprehensive regulatory package. As part of the package, the nominal thresholds prescribed in the Borrower-based rules will be modified as of 1 January 2026, while the requirements applying to the loan-to-value ratio for first-time home buyers were modified with effect from September 2025 in order to make the lending processes smoother.

3.1. With the current expansion of household lending, borrowers’ income burden is on the increase, but it cannot be regarded as excessive yet

Household lending grew dynamically during 2025 H1. Banks disbursed household loans in an amount of about HUF 1,648 billion during that period (Chart 6), up to 33 per cent year-on-year. In the first half of the year housing mortgage lending amounted to HUF 808 billion, exceeding the all-time high recorded in 2022 H1 and up to 26 per cent year-on-year. Consumer lending increased by an even more remarkable 41 per cent during the same period, partly as a result of the introduction of the so-called Subsidised Loans for Workers Programme, which amounted to HUF 107 billion new loans in just half a year. Personal loans grew by 40 per cent year-on-year, while the amount of prenatal baby support loans dropped by 13 per cent. In spite of the rapid credit outflow, the volume of household lending – adjusted for inflation – increased by less than 2 per cent relative to the amount recorded in 2020 H1; therefore, the robust nominal growth in lending does not, in itself, constitute a risk factor.

Chart 6: The development of new household lending by loan type

Note: Credit institution sector. Without individual entrepreneurial loans. Source: MNB

The volume-weighted average of debt-service-to-income ratio (DSTI) has increased in 2025. The volume of household loans, which is clustered around the DSTI limits, has been gradually expanding, in particular, in the housing loan segment. While in 2019, banks disbursed about 20 per cent of housing loans at a high DSTI of over 40 per cent, in 2025 H1, this proportion nearly doubled, ending up at 36 per cent (Chart 7). Due to steady house-price increase, and an increase in repayment costs caused by still high e housing loan rates despite of the normalisation process, the income burden is growing by volume. This process is also driven by the fact that the higher – 60-per-cent – DSTI limit applying to borrowers with incomes exceeding HUF 600,000 is becoming accessible for more and more borrowers as a result of the rapid increase in nominal wages that has been observed during the recent years (the effectiveness of the DSTI income limits is discussed in detail in Sub-chapter 2.3). Nevertheless, the risks stemming from the DSTI burden are mitigated by the fact that in terms of the number of contracts the income burden has been growing less dramatically; in other words, the risk of income-stretched loans is associated with a smaller group of borrowers, many of whom are in a better than average income position and apply for loans of larger than average amounts.

No further increase in collateral encumbrance is currently envisaged but seems to be likely in a longer run. The weight of housing loans with low down payment, i.e. with loan-to-value ratios (LTV) over 70 per cent in new loan disbursements was about 30 per cent in 2025 H1, more or less the same as during the corresponding period of 2024. Looking forward, however, loans disbursed with lower down payments may increase collateral encumbrance through the expected increase in the number of first-time home buyers entering the market due to the Home Start Programme; therefore, the housing loan market processes need increased monitoring.

Chart 7: The development of new residential mortgage lending near borrower-based measures limits

Note: By volume: * Overlap is possible between loans granted with DSTI above 40% and LTV above 70%. Source: MNB

On the whole, household lending is currently taking place in a healthy structure, in accordance with the borrower-based measures, denominated in forints and with interest rates fixed over longer period. However, borrowers’ income stretch is on the increase gradually and steadily. Therefore, the MNB continuously monitors the changes in the lending processes, partly in view of the potential rise in demand for loans under the Home Start Programme.

Regarding the rise in real estate market risks, in September 2025, the MNB adopted a comprehensive package of proposals to tackle mortgage loan market risks. This included decisions on raising the nominal thresholds relating to the DSTI requirement, and on fine tuning the loan-to-value requirement to be met by first-time home buyers.

3.2. The increased LTV limit applying to first-time home buyers did not result in a material rise in credit risks

The MNB imposed a lower down payment requirement, i.e. a higher, 90-per-cent loan-to-value limit, for first-time home buyers from 1 January 2024 and for green real estates from 1 January 2025. In 2024, loans provided for first-time home buyers with 80–90-per-cent LTV ratios accounted for about 4 per cent of the total new residential mortgage lending, comprising 1,700 transactions, while the total number of loans provided for first-time home buyers is estimated to have been around 10,000. Accordingly, some 15–20 per cent of first-time home buyers eligible for the higher LTV limit may have taken out their housing loans with less than 20-per-cent down payment. The proportion of loans provided in 2025 H1 with 80–90-per-cent LTV ratios was somewhat higher than 5 per cent (Chart 8, left-hand-side panel), partly because of the higher LTV limits made available from the beginning of 2025 for green loan purposes. Of the total portfolio of loans provided, most – some 4.8 per cent – of the loan applications submitted with LTV ratios over 80 per cent had been extended to first-time home buyers, 3.2 percentage point of which were green loans. On the other hand, in 2025 H1, the proportion of green loans applied for with over 80-per-cent LTV ratios by non-first-time home buyers was a marginal 0.4 per cent of the total new residential mortgage lending (Chart 8, right-hand-side panel).

Chart 8: The development of new residential mortgage disbursements by volume according to LTV (left panel) and by first-time buyer and green status in the first half of 2025 (right panel)

Note: In the right panel, the categories First-time buyer, Green, and First-time buyer-Green show the borrowers taking advantage of the discount. Source: MNB

The data of the first 1.5-year of the preferential rules show that first-time home buyer LTV requirement probably came as a considerable help to young borrowers with limited funds of their own but adequate income, in achieving their housing objectives. The income of first-time home buyers is usually not as stretched as that of a non-first-time home buyer borrower, partly because of the higher proportion of borrowers not having any loans among first-time home buyers (Chart 9, right-hand-side panel). Thanks to the lower interest rates and, consequently, to the larger accessible loan amounts, the proportion of first-time home buyers making use of the over 80-per-cent LTV in the case of state subsidised loans is higher (22 per cent) than in the case of non-state subsidised loans (12 per cent). No material geographical differences by collateral encumbrance can be identified.

Owing to the borrowers’ lower income stretch, the limited volume of such loans within the total residential mortgage lending and the presumably lower credit risk associated with the customers concerned; therefore, the more favourable LTV limit introduced for first-time home buyers does not result in any material increase in the systemic risk, on the whole.

Chart 9: The evolution of new mortgage lending contract by income (left panel) and by DSTI (right panel)

Note: Data for 2024 and the first half of 2025. Source: MNB

The Home Start Programme – launched in September – may drive the proportion of loans with low down payments in the total volume of new loans even higher. On account of the favourable interest rates available under the Home Start Programme in the case of the eligible borrowers, the amounts borrowed is expected to be maximised relative to the borrowers’ income positions and the collateral concerned, which may lead to an increase in collateral encumbrance and in the proportion of loans provided with high – 80–90-per-cent – LTV ratios. However, the risks of the processes are mitigated by the product’s interest rate which is lower than the market rate and fixed for the entire term, along with the lower income burden of first-time home buyers than that of other borrowers.

To ensure smooth lending processes, the MNB modified the conditions for the accessibility of the higher LTV limit for first-time home buyers on 1 September 2025. Under the modification, the MNB removed the 41-year age limit prescribed in relation to the 90-per-cent loan-to-value limit pertaining to first-time home buyers with effect from 2 September 2025. The removal of the age limit supports the smoothness of the lending processes in the evolving market environment without triggering an increase in risks, since the higher LTV limit will continue to be accessible for customers with shares of ownership below 50 per cent, wishing to make their own homes and, therefore, more willing to repay their loans. The efficiency of lending processes will be improved by lenders having to identify first-time home buyers who are eligible to higher loan-to-value ratio limit, with significantly less cumbersome administrative formalities, by querying from the land register, from December 2025.

3.3. The MNB continuously monitors the efficiency of and institutions’ adaptation to the borrower-based rules, and is fine-tuning the regulation as necessary

The nominal wage increases during the past two years are eroding the effectiveness of the DSTI income threshold, which may drive lending risks up. The DSTI income threshold set at HUF 600,000, allowing a higher-than-50-per-cent income burden, was last revised in July 2023. The average income of mortgage loan borrowers, during the more than two years since then, has increased from HUF 746,000 to HUF 875,000. The proportion of borrowers eligible for the 60-per-cent DSTI limit has, in the meantime, increased from 65 per cent of new housing loans in 2023 to 80 per cent in early 2025. The increase in the percentage of borrowers eligible for the higher DSTI limit has been accompanied by a rise in the actual usage of the limits: the proportion of new loans with higher-than-50-per-cent DSTI has increased from around 10 per cent in 2023 to 12 per cent (Chart 10).

Chart 10: The development of new residential mortgage disbursements by DSTI income

Note: By volume * 2025 first half data. Source: MNB

To maintain the effectiveness of the DSTI requirement the MNB has raised the DSTI income threshold. In view of the dynamic nominal wage increases that have been observed during the past years and that are expected to continue, the MNB has adopted a decision on raising the DSTI income threshold from the current HUF 600,000 to HUF 800,000 with effect from 1 January 2026. The raising of the income limits is justified by both the increase in the nominal incomes and borrowers’ growing income burdens. The raising of the DSTI income threshold helps to prevent over-indebtedness without material negative impacts on the credit market, by withholding excessively risky loans.

No material increase in the financing of down payments with uncovered personal loans is experienced. The share of personal loans disbursed 180 days prior to taking out a housing loan, which is likely to finance the down payment, or the associated costs of home purchase is stable at 3–4 per cent of residential mortgage lending from 2020 H2 (Chart 11). The decrease was supported by the MNB’s executive circular issued in 2019 for institutions as a guidance for the assessment of own contributions (available in Hungarian only), the prenatal baby support loans available from 2019, and the higher LTV limits made available for first-time home buyers from the beginning of 2024.

Chart 11: Estimated development of personal loans used to replace self-reliance

Note: The ratio of mortgage lending by contract number within the disbursement of each LTV category, for which the principal debtor took out a personal loan as well maximum 180 days before the conclusion of the mortgage contract. Without prenatal baby support loans. Source: MNB

As regards housing loans, the shift towards longer-term loans by borrowers with a high income burden appears to be stabilising. Borrowers can also adjust to high repayments by extending the maturity. The difference between the average maturity of income-stretched housing loans with a DSTI above 40 per cent and that of housing loans with lower DSTI, is around 3.5 years in 2025 H1 like in earlier years; the proportion of loans with shorter than 15-year terms among loans with higher-than-40-per-cent DSTI decreased somewhat (Chart 12). However, the average maturity is not considered risky even in the case of the 20.4-maturity that is characteristic of more income-stretched loans. No significant maturity extension was observed for consumer loans.

Chart 12: Development of the maturity of housing loans at the time of contract conclusion according to DSTI stretch

Note: For 2025, data refer to the first half of the year. Includes only housing construction and purchase loans, excluding renovation and expansion purposes. The violin plot illustrates the distribution of data by loan maturity, while the box plot shows the interquartile range (IQR) and the 1.5×IQR values. Source: MNB

BOX II: Model development efforts aimed at strengthening the housing market risk monitoring system

An excessive and persistent increase in house prices and households’ related indebtedness may trigger the development of massive systemic risks in the financial system. As precise and as rapid forecasting of housing price dynamics as possible may thus contribute significantly to the development of more effective and rapid policy responses. However, due to the rapid changes in the economic environment and occasionally to substantial delays in reporting, conventional models that are based on quarterly data can only indicate the build-up of risks with significant delays. In response to these challenges the MNB has developed an advanced 2-pillar modelling framework which provides for more accurate and timely support for decision making.

The MNB’s monitoring system for housing market forecasting relies on two mutually complementary econometric models:

The primary purpose of the earlier developed Lasso quantile regression model (QR Model), presented in the May 2025 Housing Market Report, is to map risks and extreme outcomes, rather than the central trajectory. The “LASSO” procedure in the name of the model is an automated variable selection technique that is capable of selecting, from the potential explanatory factors, the ones that are the most relevant to housing price dynamics, making the model even more robust. Its key characteristic is that it is capable of providing stable forecasts particularly during periods of high volatility and uncertainty when the assessment of downside risks is most critical. The model enables quantification of the “House-price-at-Risk” (HaR) type risk indicators showing the potential extent of a negative market shock.

The key innovation of the other newly developed mixed frequency Bayesian state-space model (MF-BVAR) is bridging the information gap between different data supply cycles. The Bayesian approach improves the model’s performance particularly in cases when work is carried out with a large number of explanatory variables and relatively short time series, as is often the case in housing market modelling. The model utilises information on data series persistence with the help of the so-called Minnesota prior which is capable of efficiently managing large numbers of parameters to be estimated, thereby improving the accuracy of forecasting. The model analyses the evolution of house prices in a complex system consisting of twelve variables, combining quarterly data (e.g. MNB house price index, long-term unemployment) with monthly indicators (e.g. credit outflow, transaction number, financial stress index). The model is thus ideal for nowcasting, i.e. for highly accurate forecasting of housing price dynamics for the current quarter, thereby enabling more accurate short-term forecasting of the most likely housing price trajectory. This enables decision makers to work with a nearly real-time picture of the current state of the market. Two separate models have been developed in order to forecast national and Budapest housing price trends, incorporating data specific to Budapest (where available) in the case of the capital.

The mixed frequency MF-BVAR model enables more accurate forecasts by using longer time series. To verify the effectiveness of our forecast, we also worked out our forecast for the capital city, starting from 2024 Q2 and Q4. In the case of the forecast starting in 2024 Q2 (Chart 1, left-hand-side panel), where the MNB’s nominal house price index data are available until 2024 Q1, the longest one of the monthly data series lasts until August 2024. In this case the forecast produced by the QR model is also close to the MF-BVAR median estimate, within its 20–80-per-cent confidence range. In the case of the estimate starting in 2024 Q4 (Chart 1, right-hand-side panel), where the MNB nominal house price index is available until 2024 Q3, the MF-BVAR model forecast remains close to the actual data on account of the use of monthly information which continues to be available for another four–six months, while the QR model forecast, which uses only quarterly data, i.e. less information, lags significantly behind the MF-BVAR model forecast and the evolution of the actual data. These two estimates indicate the necessity of the mixed frequency model and the scenario in the case of which it provides significantly more accurate forecasts than quantile regression does. No major trend reversal was observed in real estate prices in 2024 Q1, but the increase of prices accelerated significantly from 2024 Q3. In the latter case it was largely due to the use of monthly data available in near real-time that the forecast followed the acceleration of the price rise with a 1-month lag, i.e. almost in real-time.

Chart 1: Mixed frequency forecast of the Budapest MNB house price index starting from the second quarter of 2024 (left panel) and the fourth quarter of 2024 (right panel)

Note: All time series start in January 2013 in the mixed frequency model. The end date of the monthly data is not balanced, for example, in September 2024 it changes between June and August 2024, while the quarterly data, including the MNB house price index, were available in the same time window until the first quarter of 2024. Our model cannot explicitly take into account the impact of the Home Start Program in September in the latest data update, as it is a time series model and is based on past data, but the recently increased demand is already reflected in the results. Source: MNB

The application of the two models together provides a completer and more reliable picture of the housing market processes. Their close interrelationship is indicated by the fact that the set of variables used in the MF-BVAR model was worked out on the basis of the Lasso model’s variable selection results. The mixed frequency model thus sets out the most probable short-term trajectory of house prices, while quantile regression plots the risk zones along this trajectory. This dual approach directly contributes to a more effective macroprudential policy, since the forecasts based on near-real-time data serve as early warning signals, enabling proactive response. Moreover, knowledge of both the central trajectory and the level of risks helps to fine tune the macroprudential instruments (e.g. borrower-based measures).

4. Basel liquidity and funding rules

The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) – which ensures the banking system’s short-term liquidity on the regulatory side – was at a stable high level during the past year, although with a modest decrease in the liquid asset surplus. The decrease in liquid assets, and their internal restructuring, continued to dominate the development of the sector-level LCR over the past year, particularly as a consequence of the decline in bank liquidity in the central bank’s reserve account, which exceeded the increase in government securities. The Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) requirement is met by the banking system with a modestly decreasing stable funding surplus in connection with the increase in the credit portfolio. The structure of stable funds is favourable, characterised primarily by a high proportion of capital-type liabilities and household deposits.

4.1. The banking sector continues to have a significant short-term liquidity surplus

The LCR – which ensures the banking system’s short-term liquidity on the regulatory side – was at a stable high level during the past year, although with a modest decrease in the liquid asset surplus. After a modest decrease in the past year, the sectoral LCR calculated on individual compliance is still high: 166 per cent according to data as of 30 June 2025 (Chart 13). The banking system’s consolidated LCR was 189 per cent during the same period. During the 1-year period covering the first half of 2024 and the second half of 2025, every individual bank achieved LCR levels of 130 per cent, along with consolidated compliance levels of over 140 per cent, typically in connection with a modest decline in – primarily maturing collateralised long-term MNB – loans. Although every bank complies with the regulatory requirements, liquidity in the banking system is not evenly distributed among the institutions, which may, in some cases, require more active liquidity management. The entire banking system has a surplus of liquid assets in an amount of about HUF 7,400 billion, in excess of the 100-per-cent minimum requirement. According to the MNB liquidity stress test results the liquidity surplus of the domestic banking sector would sufficiently cover the regulatory requirements even in the case of a severe stress.2

Chart 13: Development of institutions’ LCR

Note: The 10th and 90th percentile, first and third quartile values and averages are represented, based on solo compliance data. Excluding mortgage banks and housing savings banks. Source: MNB

Significant changes can be observed in the factors – primarily in liquid assets – determining the evolution of the LCR and its long-term structural change. The decrease in the volume of liquid assets and their restructuring have been driven during the recent period by the diminishing of the stock of central bank discount bills held by banks on their own accounts (central bank assets), the shrinking of banks’ liquidity held on the central bank reserve account (withdrawable central bank reserves) and a lower rate of increase in the MNB's eligible government securities holdings (general government assets). The latter may have been driven by the optimisation of banks’ extra profit tax, resulting, for instance, in a decline in the stocks of central bank discount bills held by banks on their own accounts (Chart 14).

Chart 14: Development of LCR's liquid assets and net outflows

Note: Liquid assets calculated based on solo compliance. Data excluding mortgage banks and housing savings banks. Source: MNB

Banks are adequately meeting the additional LCR liquidity requirements imposed by the MNB in 2023 under its supervisory powers. The MNB’s extra supervisory requirements regarding the LCR as laid out in its August 2023 executive circular, including those pertaining to 140-per-cent LCR compliance, tighter liquidity management and, in particular, the Pillar 2 liquidity buffer requirements, mainly related to deposit concentration, are still in effect. In the wake of this additional liquid asset requirement, necessitated by the extra outflow to be booked in relation to the risks of large deposits, demand for extra liquid assets in an amount of about HUF 1,200 billion had accumulated, thanks to 60 per cent of the individual banks, by 30 June 2025, equalling 8.5 per cent of the total Pillar 1 outflow, on an average. The requirement continued to impose a material burden primarily on smaller banks, but even certain large banks were forced to book extra outflows exceeding 10 per cent. With the Pillar 2 surplus requirement considered, the sector level LCR is, on the whole, 16 percentage points lower. However, as regards the LCR calculated with the Pillar 2 supplement, meeting 100 per cent is sufficient (Chart 15).

Chart 15: Sector-level LCR with the Pillar 2 requirement

Note: Calculated sectoral averages based on solo compliance. Source: MNB

The level and structure of liquidity may be affected by a variety of factors in the shorter, and in a longer term, no material decrease in significant liquidity surpluses is expected. The decision adopted by the MNB in July 2025 on reducing the mandatory reserve rate from 10 per cent to 8 per cent may continue to support the restructuring that determines the structure and level of liquid assets, though it may be regarded overall as an LCR-neutral one. The central bank’s long-term collateralised loans also began to mature in March 2025, whose impacts on liquidity and the LCR may be more negative depending on the extent to which the instant decrease in liquidity is offset by the conversion of assets released from collateral (primarily government securities) into liquid assets. Data showed that a few large banks had no or hardly any actually encumbered government securities left; therefore, the repayment of the MNB loans tended rather to reduce the LCR. In a longer run, on the other hand, the transfer of the deposits of municipal governments to MÁK (Hungarian State Treasury) accounts in several stages from October 2025 may bring about structural changes and a modest decrease in liquidity in the sector.

4.2. Banks have an adequate funding structure and stable funding

The EU-wide NSFR requirement for long-term stable funding is met by banks with significant, although marginally decreasing surpluses. The required 100 per cent was delivered by the banks in the past year in terms of individual compliance at a sector-level with a modest decrease, at 132 per cent according to data as of 30 June 2025, with a minimal decrease also in consolidated compliance. Accordingly, the sector-level stable funding surplus decreased by 6 per cent in one year to HUF 11,650 billion at end-June 2025, due to the growth in the demand for stable funding induced by an upswing in lending. The overwhelming majority of large banks had a way more than safe – 15 per cent in terms of individual compliance, or 29 per cent in terms of consolidated compliance – surplus of stable funding, significantly exceeding the minimum required levels (Chart 16).

Chart 16: Development of institutions’ NSFR

Note: Lower and upper deciles (dark blue lines), lower and upper quartiles (light blue bars), and median values (mean and median), based on solo compliance data. The NSFR came into force on 28 June 2021, up to that date estimated numbers (coloured area). Source: MNB

The modest decrease in the sector-level NSFR was a result of an increase in demand for stable funding in connection with asset side changes, stemming from an upswing in lending. The 2-per-cent increase in the sector’s demand for stable funding took place with an unchanged stock of net stable funds. The rate of the gross asset side growth determining the demand for stable funds also exceeded the rate of the gross liability side growth. The asset side was dominated by the increase in loans outstanding and in the stock of liquid assets generating low demand for stable funds. The dominant factors on the liability side included primarily household deposit and, secondarily, the increase in stable funding stemming from an increase in equity-type liabilities, exceeding the decrease in funds from financial customers by far. Overall, both the average risk weight of the facilities determining the demand for stable funding and the average stability factor of stable funds decreased by more or less equal rates during the 1-year examined period.

4.3. The domestic banking system is characterised by a significant liquidity and funding surplus even in international comparison

The position of the domestic banking system is considered good even relative to other EU Member States in terms of the two Basel type funding requirements, the LCR and the NSFR. As regards consolidated compliance: a comparison to the available EU data as at the end of the second quarter of 2025, clearly shows that both the domestic LCR (191 per cent) and the domestic NSFR level (147 per cent) for the same period are materially higher than the corresponding EU average ratios, and even higher than those of most of the Visegrád countries (Chart 17). The domestic banks’ loans to deposits ratio calculated by the EBA for non-financial enterprises and households as an average funding risk indicator (80.6 per cent) is way below the EU average (106.4 per cent), indicating a massive free lending capacity.

Chart 17: LCR and NSFR compliance of the domestic banking system in EU comparison

Note: Consolidated compliance, narrowed bank-based compliance except for Hungary, where data refer to the entire sector. In the case of PT, SI, CY, MT and LT, LCR averages above 250 percent are not shown for comparability. Data sorted by LCR levels. Source: EBA Risk Dashboard, MNB

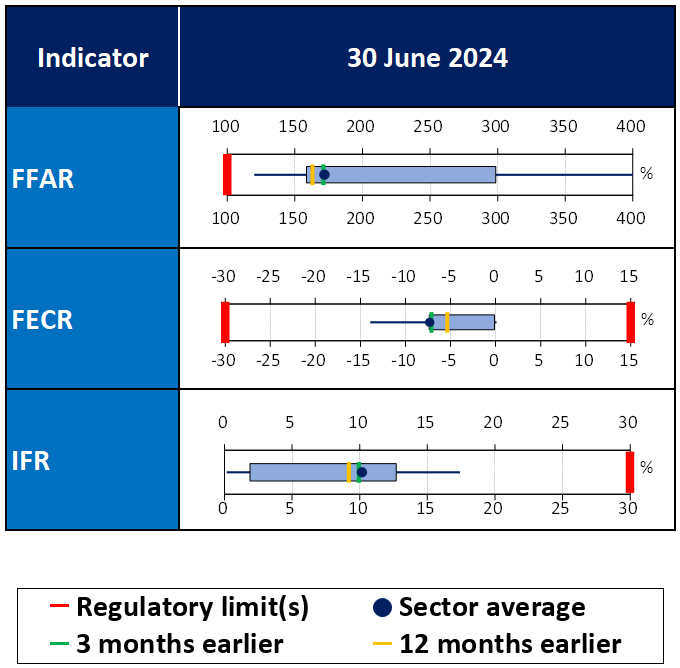

5. Instruments mitigating external vulnerability (FFAR, FECR, IFR)

The banking system’s short-term external debt as a proportion of its balance sheet total, and in connection with this, its external vulnerability, remains low in historical comparison. The national macroprudential requirements aimed at managing financing risks that are not, or that are only indirectly managed by the Basel standards, are met by the banks using safe buffers, in a healthy financing structure. The MNB did not change the financing toolkit in place to reduce short-term external vulnerability.

5.1. Systemic risk associated with external vulnerabilities of the banking system is moderate

The banking system’s systemic vulnerability associated with the short-term external debt continues to be historically moderate. The banking system’s short-term foreign debt denominated in euros had reached the year-2007 level by the end of second quarter of 2025. This, however, was through a small increase relative to the banking system’s balance sheet total or the GDP. According to preliminary figures the domestic banking system’s short-term debt – in terms of remaining maturity – amounted, at the end of second quarter of 2025, to EUR 9.9 billion, accounting for 5.0 per cent of the banking system’s balance sheet total, a little below the corresponding figure of the previous year. Although 2 percentage points over the all-time minimum, it is way below the maximum recorded in 2010 (Chart 18). The short-term external debt continues to be concentrated in the banking sector, and it is volatile in connection with certain less risky intra-group transactions of the few banking groups concerned.

Chart 18: Development of banking system short term debt

Note: SED – short-term external debt, GDP – gross domestic product, BST – balance sheet total, RES – international reserve. Credit institution sector, including MFB and KELER data. Historical minimum values, from first quarter of 1998. Source: MNB

5.2. The banking system meets domestic funding requirements with adequate buffers and a secure funding structure

The elements of the macroprudential toolkit targeting the external, foreign exchange and interbank financial risks of the banking system are met by the sector with safe buffers. Banks have a considerable manoeuvring room for lending and for the management of any funding shock in relation to the regulatory requirements applied domestically to complement the EU-level Basel liquidity funding requirements (LCR, NSFR) owing to country-specific risk characteristics (Chart 19). Significant buffers, proven to have been stable retrospectively in the short-term and the long-term as well, minimise the likelihood of funding problems akin to the challenges posed by the previous financial crisis.

Chart 19: Compliance of the banking sector with the liquidity and financing requirements

Note: FFAR - Foreign exchange Funding Adequacy Ratio, FECR - Foreign Exchange Coverage Ratio, IFR - Interbank Funding Ratio, MFAR - Mortgage Funding Adequacy Ratio, LCR - Liquidity Coverage Ratio, NSFR - Net Stable Funding Ratio. The edges of the blue rectangles indicate the lower and upper quartiles of the distribution, and the ends of the dark blue lines indicate the lower and upper deciles. For LCR, excluding mortgage banks and housing savings banks, based on solo compliance data. For NSFR, including mortgage banks and housing saving banks, based on solo compliance data. Source: MNB

The banking system is operating with significant foreign exchange surplus that is safe and of a favourable structure from the aspect of the Foreign exchange Funding Adequacy Ratio (FFAR) and the Foreign Exchange Coverage Ratio (FECR) rules. The sector-level FFAR was at a historic high during the past year as well, and at end-July 2025, it was up at 172 per cent with an approx. HUF 6,500 billion stable funding surplus. The foreign currency liability surplus to total assets ratio also stabilised, and at the end of July 2025, the FECR was at -7 per cent, conveniently in the acceptable from -30 to +15-per-cent range. At the end of the examined period, the banking system had a total amount of HUF 4,900 billion in the way of on-balance sheet foreign exchange funding surplus. The development of both the FFAR and the FECR is indicative of the banking system’s stable financing processes.

Despite quarterly fluctuations, fundamental stability is observable in the internal structure of increasing required stable foreign exchange funding considered in the calculation of the FFAR (foreign exchange assets to be funded) as well as the even more remarkably growing available stable foreign currency funds. The volume of customer deposits – in particular, the volume of corporate deposits placed by non-financial enterprises other than SMEs as well as the volume of short-term non-bank financial enterprises linked, for the most part, to investment funds, as well as their share of stable funds – increased on the liability side. The share of foreign exchange liabilities with a maturity over one year also increased moderately, in connection with the above changes. On the assets side there was a material increase in both the volume and the share of corporate foreign exchange guarantees and credit facilities, with a marginal impact on the FFAR due to the 0 or very small weights applied to the extent to which they are taken into account, i.e. they had no or hardly any impact on the demand for stable funds. (Chart 20).

Chart 20: Asset and liability groups requiring and ensuring stable financing, as well as development of financing ratios

Note: Based on unweighted items of the FFAR. Between March and September 2020 temporary tightening was in effect in case of FFAR and FECR. A: assets, L: liabilities. Source: MNB

In connection with the on-balance sheet open position, the banking system has an off-balance sheet FX swap market net forint fund raising exposure (Chart 21). The market, counterparty and liquidity system risks associated with swap market exposures are manageable. Although at a historic high in terms of volume, the FX swap market turnover (market size) is definitely low relative to the balance sheet total. The MNB’s FX swap facility continues to provide security on the forint-earning side.

Chart 21: Development of on-balance sheet FX and FX swap position aggregates

Note: A negative FX swap position covers a forint-gaining FX swap position. Source: MNB

The sector-wide reliance on riskier corporate funding remained stable at a low level, well below the 30-per-cent maximum permitted by the Interbank Funding Ratio (IFR) requirement. At the end of the second quarter of 2025, the sector-level average was the low level of 10 per cent, more or less unchanged year-on-year. (Chart 22). Most banks, including the large ones, comply with the requirement with significant buffers. Apart from one foreign-owned banking group relying exclusively on short-term funds as regards its interbank funds, larger branches continue to be operating with smaller free manoeuvring rooms, with the highest and most volatile ratios resulting from concentrated intra- and extra-group transactions. The share of funds of higher risk targeted by the IFR in corporate finance increased moderately, i.e. the share of exempted special funds with a lower risk decreased in the past year. On the other hand, the proportion of more volatile short-term exposures – including both those in forints, and those in FX – increased within the funds covered by the IFR, which was reflected in a smaller increase in the indicator due to higher weights. However, despite a small, unfavourable internal structural shift and also in view of the larger share of market finance, the reliance on funds from financial corporations does not show any significant increase in vulnerability due to the relatively low-level funds from financial corporations.

Chart 22: Development of the banking system's funds from financial corporations targeted by IFR

Note: Funds from gross unweighted financial corporations. Gross IFR is unweighted IFR-targeted financial corporation funds over all liabilities. Exempted funds: mortgage-backed funds, loans received from special institutions, funds from foreign branches of credit institutions, bonds with a maturity exceeding 2 years at the time of issue, balances of margin accounts, additional capital stock, funds received from credit institutions belonging to the group (not from the parent company), financial derivatives within the fair balance source side value. Source: MNB

6. Mortgage Funding Adequacy Ratio (MFAR)

Banks comply with the Mortgage Funding Adequacy Ratio (MFAR) regulation with safe buffers. The past year has seen a further – though modest – increase in the amount of domestically issued mortgage bonds. The share of green mortgage bonds decreased somewhat in spite of the growth in volume, while the share of the foreign currency stock increased considerably as a result of another massive foreign currency mortgage bond issuance abroad, which reduces the potential concentration risks by ownership diversification. Due to unfavourable conditions in the mortgage bond market, the MNB previously postponed several tightening measures and even took targeted measures. However, as a consequence of the massive growth in residential real estate lending that has been triggered by the launch of the Home Start Programme, a material increase in the stock of mortgage bonds is expected. Partly in response to this, the MNB has resolved to strengthen the regulation in place to ensure stable funding of mortgage loans.

6.1. The MFAR regulation is an effective tool for long-term, stable funding of banks and the development of the mortgage bond market

Together with the central bank’s mortgage bond purchase programmes the MFAR regulation has, during the past nearly ten years, contributed to the improvement of the banking system’s balance sheet maturity structure and, consequently, to the strengthening of financial stability, while it has also promoted the development of the domestic mortgage bond market. Instead of three, there are five specialised banks – mortgage banks – on the market issuing mortgage loans and providing refinancing services. The stock of mortgage bonds doubled – from the approx. HUF 1,000 billion recorded in 2015, it grew to HUF 2,345 by 30 June 2025 (Chart 23). As a result, the stock of mortgage bonds as a percentage of the total household sector mortgage loan stock doubled in the past decade, to 35 per cent at the end of second quarter 2025.

Chart 23: Development of mortgage bonds and mortgage bond/mortgage loan rate

Note: Mortgage bond stock projected to mortgage loans, calculated with the mortgage bond stock based on nominal value data, using an unweighted denominator and numerator. Source: MNB

The MFAR requirement is met by the banks and by the whole sector with significant buffers. The banking system’s MFAR average stood at 31.7 per cent on 30 June 2025 (Chart 24). On 31 March 2025, the ratio dropped to its 5-year low – at 28.5 per cent – because the banks typically delayed their new issues due to the uncertain conditions and the substantial existing surplus funds, in spite of the substantial maturing stocks and the increase in the existing mortgage loan stocks. However, overall, due to the long-term nature of this type of financing, it is a less volatile regulatory requirement, one that is highly predictable and depends primarily on the development of loan portfolios and the maturity of mortgage bonds (and related refinancing). This enables the mortgage bond issuances and refinancing relationships ensuring compliance to take place under the best possible conditions and at the most optimal time.

Chart 24: Development of MFAR compliance

Note: Mean, 10th and 90th percentile, 1st and 3rd quartile. Source: MNB

6.2. Some minor changes were observed in the characteristics of the mortgage bond portfolio, to a considerable extent was induced by the MFAR regulation

Over the past year, the total stock of mortgage bonds, including green and foreign currency mortgage bonds, has grown, which has also shifted the ownership distribution in a positive direction. Growth continued to be supported primarily by the MFAR regulation and the possibility of renewing mortgage bonds with the central bank. 12.5 per cent of the total stock was made up of green forint mortgage bonds, and in the wake of the second large non-green foreign currency mortgage bond issue, the stock of foreign currency mortgage bonds increased to 17 per cent. Every bank has green mortgage bonds now, while only one bank has issued foreign currency mortgage bonds. On the whole, the developments observed in recent years have contributed to both the diversification of mortgage bonds and keeping a wide range of investors interested in this particular form of investment (Chart 25).

Chart 25: Evolution of the stock of domestic mortgage bonds by currency and sustainability

Note: Based on data at nominal value. There are no green foreign currency mortgage bonds on the market for the time being. Source: MNB

As regards ownership structure, there is still considerable room for attracting stable funding actually from outside the sector, but the increase in the share of institutional and foreign market players outside the domestic banking sector is considered as a favourable development. On the assets side, banks continue to hold substantial mortgage bond portfolios. On the one hand, banking groups tend to hold considerable portfolios of own-issued securities, and on the other hand, banks’ mortgage bonds are also typically held on the assets side. As a consequence of the limited asset purchase programme – that has, for several years, been limited exclusively to the renewal of mortgage bonds, and that was not fully utilised on several occasions during the past year – the MNB’s share of ownership has halved since 2022. This decrease was less salient in the green mortgage bonds segment (Chart 26). In relation to the foreign currency mortgage bond issues, it should be noted that in line with the objective of the regulatory amendment enabling them to be taken into account in the MFAR calculation, the share of foreign ownership is increasing, with a significant and diversified composition of foreign banking and other financial intermediary investors not related to domestic banking groups.

Chart 26: Mortgage bond portfolios broken down by main ownership sectors

Note: Data at face value. Domestic institutional investors: other financial intermediaries, financial auxiliaries, insurance companies and pension funds. Other domestic investors: non-financial corporations, households and non-profit organisations serving households, general government subsectors. Source: MNB

The mortgage bond market is expected to grow even with regulations remaining unchanged. Years 2025 and 2026 will see the maturity of mortgage bond portfolios smaller than those that matured in previous years: HUF 269 billion in 2025 and HUF 98 billion in 2026. At the same time, in view of the upswing in mortgage lending and, in particular, the Home Start Programme, a significant expansion – of a hitherto unknown scale – of the mortgage loan portfolio is to be expected. This will generate substantial demand for bond issues: to keep up the current levels of MFAR compliance new mortgage bonds in a total amount of HUF 500–700 million may appear on the market in 2025 and 2026 according to conservative expectations – or even as much as HUF 900–1,300 billion if driven by more vigorous outflows –, depending on whether mortgage banks issue green mortgage bonds that can be taken into account in the MFAR calculation with a favourable weight, or they decide to issue brown securities instead (Chart 27). However, about half of these, or even less may be sufficient for meeting the 25-per-cent MFAR minimum as required by the regulator, but in a distribution between other banks, on account of the different MFAR surpluses.

Chart 27: 2025-2026 issuance needs with different JMM compliance targets and mortgage bond types under different loan growth assumptions

Note: Estimate based on MFAR data as of June 30, 2025. Taking into account the projected growth of loan portfolios in the MFAR denominator for the second half of 2025 and the entire 2026, including the impact of the Home Start loan program. In terms of the issuance requirement, we also took into account the adjustment needs of other banks through refinancing relationships. Source: MNB

6.3. A revision of the MFAR regulation became necessary partly in view of mortgage lending processes

The increase in mortgage lending, the MNB’s mortgage bond market development goals and the need for further reduction of the associated systemic risks called for a revision of the regulation. The MNB is operating the regulation in a flexible way, in view of its financial stability and monetary policy objectives, the relevant market processes and its own market development goals. In view of changes in the fundamentals affecting the regulation and compliance with it, in September 2025, the MNB determined that the regulation was in need of a revision. Accordingly, at end-October 2025, the MNB amended the relevant decree by reactivating, with effect from 1 October 2026, the provision aimed at discouraging cross-ownership between banks, which was suspended earlier in relation to the coronavirus pandemic; trading on regulated market will be a requirement applying to new MFAR funds; non-mortgage bond type collateralised securities and securitised structures will also become eligible for being taken into account for the purposes of MFAR compliance. Moreover, the central bank also raised the de minimis limit applying to the over-year mortgage loan portfolio, which ensures the exemption of smaller institutions. The amendments allow adequate preparation time for banks for adaptation, which will impose negligible burdens on them.

7. Capital buffer of systemically important institutions (OSII-B)

The MNB's annual periodic review for 2025 classified the same seven banks as in previous years to be Other Systemically Important Institutions (O-SIIs). The relatively modest change in the systemic importance and concentration of O-SII banks in the past year did not justify any change in buffer rates.

As a result of the identification process in 2024, the same seven groups of banks as last year had been classified as other systemically important credit institutions for 2025 as well. During the latest regular identification of Other Systemically Important Institutions (O-SIIs) headquartered in Hungary in 2024, the MNB continued to use the same measurement of systemic importance as in previous years, based on the aggregation of the EU-harmonised core indicators and the added optional domestic indicators. Using the audited data as of 31 December 2023, the MNB thus reviewed the O-SII scores representing systemic importance, which, as in previous years, exceeded the 275-basis-point threshold for systemic importance classification for seven banking groups (Chart 28).

Chart 28: Components of the scores of other systemically important institutions and their final buffer rates

Note: The scores shown are the results of the 2024 review. The horizontal blue line indicates the standard 350 basis points in the EBA Guidelines, while the red line indicates the domestic threshold level above which a bank is identified as O-SII, reduced to 275 basis points in 2020 as permitted by the EBA Guidelines. Source: MNB

The systemic risk footprint of the entirety of the O-SII banks stabilised at a high level, its previous growth stopped according to the 2025 scores. The total market concentration of the significant banks remained essentially unchanged in comparison to the previous year’s total score (8,025 basis points in aggregate, down by 62 basis points from the score of the previous period). As in previous years, the distribution of scores measuring systemic importance does not show a significant shift and has proved to be stable (Chart 29). The rapid growth of the OTP group had a significant impact on the components of the scores by the change in the indicators representing real economic relations, while the size, and the lending or deposit collection activities of the other O-SII banks increased only modestly, or stagnated. In addition to the slower expansion of the domestic market, the international expansion of the OTP group also expanded several components of the bank’s O-SII score, the impact of the acquisitions completed in 2023, and the outstanding growth achieved in certain other foreign markets, on the size of the group significantly outweighed effects in the opposite direction at other foreign markets where the group has presence (such as the sale of Banca Transilvania, which has already appeared in the year-end 2023 data). The evolution of the more volatile financial market and interbank indicators often only temporarily causes minor shifts in the scores. Conversely, the international expansion of the OTP group induced further structural transformation and made the group’s dominance even stronger in these indicators. The significant transformation in the network indicators of financial connectivity was the further decrease in the activity of various interbank market segments that characterized the banking system as a whole in 2023. While the volume of transactions between O-SII banks was significantly lower than in previous years, the largest branches participating in the interbank market maintained their more extensive intermediary role and increased their importance in the related sub-indicator. In the swap market network – which is also considered critical at the systemic level – the forint-side transaction volume of certain O-SII banks typically expanded significantly, either through financial relationships within or outside the international group.

At the end of 2025 Q2, banks needed HUF 675 billion in capital to meet the O-SII buffer requirement; however, they operated with a hefty free capital buffer of nearly HUF 2,218 billion, and even the lowest excess capital buffer ratio reached 4.5 per cent with significant individual differences in the capital headroom of the O-SIIs.

Chart 29: Changes in the scores of other systemically important banks

Note: The years indicate the validity period of the scores, the scores are calculated by the MNB on the basis of the audited data provided as of 31 December of the antepenultimate year. Source: MNB

BOX III: A comparative analysis of buffer rate assignment rules of the EEA Member States (“bucketing”)

The cross-country comparative analysis indicates that the calibration of the domestic O-SII buffers is balanced not only in relation to the prescribed buffer rates, but also in comparison to the buffer rate allocation rules. The required O-SII buffers show a relatively large variation between EU Member States. The significantly different regulatory risk tolerances possible between Member State calibrations have been examined on multiple occasions; for example, the EBA (2020) carried out a comprehensive assessment of the relationship between O-SII scores, serving as the primary guidance for calibration, and the O-SII buffer rates. Most recently the ECB (2025a) analysed the O-SII scores from the perspective of the Banking Union, calculating the market share-based components of the scores as a proportion of the entire Banking Union banking system instead of using the usual member state aggregates, from which it concluded that the buffer rates of the Banking Union’s O-SII credit institutions show substantial heterogeneity. In addition to the buffer rate floor assignment rule based on the scores calculated on the basis of member state banking system aggregates, which is already in effect and applicable in the Banking Union, another one will also be fully introduced by 2028, to reduce this heterogeneity. The new rule will establish minimum values (floors) for buffer rates in the Member States based on scores calculated on the basis of shares relative to the entirety of the Bank Union’s banking system instead of the Member States’ banking systems (see ECB, 2025b). From the domestic perspective, the calibration applied by the MNB was compared to those of the EEA member states by the MNB’s 2023 Macroprudential Report, demonstrating – on the basis of the joint distribution of scores and buffer rates – that the domestic buffer rates fall in the middle of the international range.

With the purpose of render the different Member State assignment rules pairwise comparable across any given range of scores, the different designs of bucketing-based assignment rules between O-SII scores and buffer rates are summarised in a single metric for each Member State, in pairs. Instead of the buffer rates specified by the macroprudential authorities, in the following paragraphs, we are going to compare those bucketing rules for buffer rate assignment that are applied by a majority of the Member States (19 authorities at present) and accessible to the public. These have been parameterized differently in the various countries, but according to the commonality in their design they all assign monotonously increasing buffer rates to the successive ranges of the scores (so-called “buckets”). Chart 1 shows such a bucketing assignment rule, more specifically the ECB buffer rate floor system used as an example. The design of the buckets typically includes a 0-per-cent buffer rate bucket, which is assigned to the score range with the lowest degrees of systemic importance (below the yellow area in the chart). This is generally followed by a segment in which the buffer rate increases step by step, where the number and sizes of buckets and the rate of the increase of the buffer rates are, for instance, designed in a country-specific way (covering the light green areas in the chart). Finally, a top bucket which contains the handful of O-SII banks, or which is completely empty, is associated with the highest buffer rate applied in the given Member State, which may in certain cases be lower than the statutory 3-per-cent minimum imposed by the CRD. In order to make the relatively large number of cross-country comparisons manageable and perspicuous, the unique structure of each bucketing design is summarised in a single metric that characterises the implied policy strictness. For this purpose the size of the area covered by the buckets is calculated, which covers a part of the plane delimited by the theoretical maximum of the score (10,000 basis points) and the buffer rates’ standard statutory maximum (3 per cent), and which can also narrowed down further to its most relevant sections populated by the O-SII banks (the areas referred to, below and above the step function-like assignment, are illustrated by colouring in Chart 1). To illustrate the working of the proposed metric of area covered with some examples, if in an extreme situation, any bank independent of its score were to be assigned the maximum 3-per-cent rate regardless of its score, then 100 per cent of the area would be covered, alternatively if they were assigned a flat 1.5-per-cent rate, the covered area would shrink to 50 per cent, finally if below 5,000 basis points banks were assigned a 1.5-per-cent rate and above 5,000 basis points they were assigned a 3-per-cent rate, then 75 per cent of the area would be covered (so the final example would be a 2-bucket structure where there is no one zero bucket up to the 350-basis point or any other threshold).

Chart 1: Illustration of a bucketing-based buffer rate assignment rule and the area covered (green) by the buffer rates, using the buffer rate floors of the ECB